The Carbon Cycle: Part One, the Water Cycle

by Gordon Maclean, Ph.D.

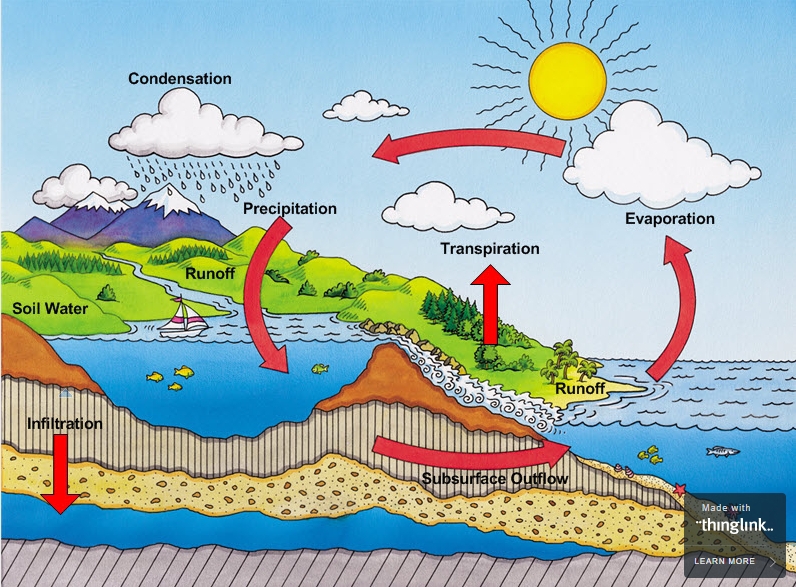

Pretty much everyone is familiar with the basics of the water cycle (or the hydrologic cycle as it is more formally called.) Rain/snow falls from the sky. It collects in puddles, goes into the ground, gathers into streams, rivers, lakes, and eventually the ocean. (See Figure 1.) After it falls from the sky, water can evaporate and goes right back into the air, where it condenses to form clouds and, if conditions are right, fall to the ground again. Hence the term "cycle."

Figure 1: The Hydrologic Cycle (drawing by Amy Boehman, www.thinglink.com/scene/355450044280733696#tlsite)

Figure 1: The Hydrologic Cycle (drawing by Amy Boehman, www.thinglink.com/scene/355450044280733696#tlsite)

The thing about the water cycle is that the water tends to collect in places. Places like lakes, in the ground, the ocean, glaciers, the polar ice caps, and even for a short time, your kitchen sink.

I put the last one in there because scientists literally call any place that water collects a "sink." A sink can be any size, from a small puddle to an ocean.

Think now of your kitchen sink. You have a way for water to get into your sink (a faucet) and a way for water to get out of the sink (a drain.) The amount of water coming out of the faucet and going into the sink has absolutely nothing to do with how big the sink is. The amount of water that leaves the drain also has nothing to do with the size of the sink.

What is important is the difference in the amount of water going into the sink versus the amount of water leaving the sink. If more goes in than leaves, the water in the sink rises until it finds another way out (maybe your kitchen floor, HORRORS.) If the water leaves the sink faster than it is coming in, the water level goes down.

The same is true with every lake and the ocean. How long it takes for water to be replaced in a sink is also very important. If the plumbing has been done correctly in your kitchen sink, the "retention time" is a matter of seconds or less. If you partially plug up the drain and turn the faucet back to a drip, the retention time can be a matter of hours.

I live just a few miles from the largest of the Great Lakes, Lake Superior. This vast water sink has numerous rivers and streams entering it, but only two ways out, the Sault Ste. Marie River at the east end, and evaporation. Scientists have measured the various streams and estimated the water from rain falling directly into the lake and compared that to the water leaving the lake and estimate that the retention time for Lake Superior is 191 years (https://www.statista.com/statistics/204184/retention-replacement-time-of-the-largest-lakes-in-the-us/).

Downstream, Lake Huron has a retention time of "only" 22 years, and Lake Erie just three years. In these cases, the amount of water going through Lake Huron and Lake Erie is about the same, but the sink's size is very different. Lake Erie is much smaller and shallower.

For the global oceans, the retention time is estimated in the millions of years. BUT there is one unique thing about oceans, the only way out is by evaporation. There is no other drain for water to leave the system.

I have not mentioned the solid form of water much here. Ice! Think of our "ocean sink" with no outlet. For ice floating in the ocean, like the Arctic Ice Cap, it's already "in the sink." However, two other huge global ice sinks are not sitting in the oceans, the Greenland Ice Cap and the Antarctic Ice Cap.

These two ice sinks have been melting, increasingly fast. As they melt, there is nowhere for the water to go, so we end up with rising ocean levels.

I have introduced many concepts here and I hope I have made them clear. Still, having read this, you are ready for the next article on the Carbon Cycle and its relation to our environment and current environmental issues.