Wolf-Moose Population Studies on Isle Royale National Park

Human Intervention Saved an Island’s Species from Extinction

Dr. Gordon A. Maclean

You could be forgiven if you have never heard of Isle Royale National Park (IRNP). It is the least visited national park in the 48 contiguous states, primarily due to its isolation and difficulty to travel there. Isle Royale is situated in the middle of Lake Superior, 70 miles from Michigan (which it is part of) and 20 miles from the Canadian shore. It’s about 45 miles long and at most 9 miles wide (about 209 square miles.) Because of its remoteness, Isle Royale has never been a permanent home for people, even in pre-colonial times.

The island is unique in many respects, and this was recognized in 1980 when UNESCO declared it an International Biosphere Reserve. Cool in summer (rarely over 80 degrees), cold but not frigid as is Minnesota to its west, both because of the moderating effects of Lake Superior.

A unique aspect of IRNP is that it is almost a closed system for large animals. That has led to the longest-running predator/prey study in the world, the Isle Royale Wolf-Moose population study.

A “closed system” is one where outside inputs are non-existent or very minimal. Moose were first noted on Isle Royale in the early 20th century, and for about 50 years, their numbers grew and shrank as weather and food supplies dictated.

I will use the term “pack” loosely here as if there is just a single pack. In reality, when the wolves on the island are in a healthy situation, there are anywhere from 4-6 actual family “packs” on the island.

From: https://www.nps.gov/isro/learn/nature/wolves.htmThen in a frigid winter in the late 1940’s an ice bridge to the Canadian mainland formed. Wolves crossed that ice-bridge and became part of the ecosystem. In 1958, researchers began the first studies of the wolf and moose populations on the island. The project started at the low point for wolf populations in North America, driven to extinction over most of their former range. The original researchers saw the potential that the closed Isle Royale system offered an opportunity to study the predator/prey population relationship without significant outside influences like pack migrations or human interferences.

From: https://www.nps.gov/isro/learn/nature/wolves.htmThen in a frigid winter in the late 1940’s an ice bridge to the Canadian mainland formed. Wolves crossed that ice-bridge and became part of the ecosystem. In 1958, researchers began the first studies of the wolf and moose populations on the island. The project started at the low point for wolf populations in North America, driven to extinction over most of their former range. The original researchers saw the potential that the closed Isle Royale system offered an opportunity to study the predator/prey population relationship without significant outside influences like pack migrations or human interferences.

Most studies of this kind go for a few years; this study has continued since its inception and has become a wealth of knowledge about how predator/prey populations self-regulate each other, with a few “wild-cards” thrown in overtime.

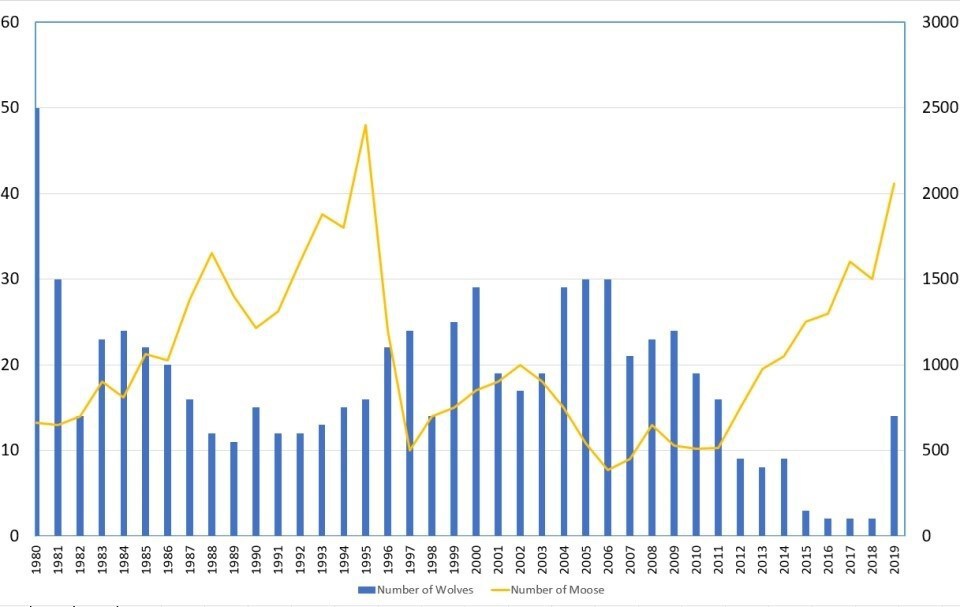

For the first few years of the study, the number of packs was increasing and so the overall population was rising. By the mid-1960s, the wolf population reached a point where there was not enough food to support their numbers, and when combined with weather factors, the populations dropped from 30 into the high teens. With less predation, the moose population exploded in the late 1960s and early 1970s, which resulted in the wolf population exploding throughout most of the 1970s, to the point where at its peak, there were 50 wolves on IRNP. In contrast, the moose population declined from 1,200 to 700.

The expectation was that the wolf population would crash in the early 1980s, but that crash was exasperated by one of those “wild-cards” that I mentioned earlier. That crash, starting in 1980, was accelerated by the accidental introduction of canine-parvovirus to the island, brought in by a visitor’s dog. Parvovirus ran rampant through the packs over the next two years, the wolf population dropped from 50 to 13, and as you might expect, that moose population took off dramatically, more than tripling from 1980 to almost 2,500 in 1995.

The following is a graph of the wolf/moose populations since the 1980 wolf population crash (wolf numbers are the bars, with the index on the left, moose numbers are shown as the line, with the index on the right.)

From: https://www.nps.gov/isro/learn/nature/wolf-moose-populations.htm

From: https://www.nps.gov/isro/learn/nature/wolf-moose-populations.htm

The wolf pack rebounded quickly. However, even given the abundance of food in 1983, the first signs of the effects of genetic issues due to inbreeding began to appear. When the wolf population dropped to only 13 in 1982, it meant that the genetics of all future generations of wolves on IRNP would be limited, coming from only a few individuals, as the pack alphas are usually the only ones to breed.

With moose numbers on the island beginning to stress the ecosystem’s ability to support them through the 1990s, moose became more vulnerable to disease and parasites. And in 1996, the moose population collapsed due to a severe outbreak of moose ticks.

Over the winter of 1997, an ice bridge formed with the mainland, and one wolf made the dangerous trek across the ice to Isle Royale. This crossing became the third “wild-card” of the study, and in hindsight, perhaps the most important to the entire study. That wolf became famous and is known as “the Old Grey Guy.” In terms of offspring, he is the most successful male wolf ever studied on the island. His interjection of genetic diversity in the packs is responsible for the bump in the numbers and health of the island’s wolf population through the early 2000s.

By 2010, the issue of inbreeding was again becoming a concern for the pack’s health. Winter after winter, no ice-bridge developed. And year after year, the pack’s genetics became more inbred, and the populations declined, with fewer pups being born and those pups suffering more and more health issues.

In 2012 the National Park Service began to consider options to revive the wolf pack, as the moose population began to rise again, unchecked. The Moose were eating themselves into another unhealthy situation as occurred in the 1980s.

Based on the 1980’s experience, the Park Service decided that it would start a program to deliberately trap and relocate wolves from various locations on the mainland (Minnesota, Michigan, and Ontario) and release them on the island. The plan was to introduce 20 to 30 wolves over several years, beginning in the summer of 2018, after the wolf population on the island had dropped to two wolves, both old and producing no new pups.

In a way, the original wolf/moose population study ended at that point. Humans opened up the closed system and essentially rebooted it. That is not to say that the science or the study stopped. If anything, it has intensified. Now the question is, can we apply what we learned after 60 years of observation and restore an out-of-balance ecosystem?

If successful in applying what we have observed, it will prove that humans are capable of restoring balanced ecosystems elsewhere in the world where that balance has been disrupted by human or natural activity and with other species that have been stressed to near extinction before their light goes out permanently.

If you are interested in learning more about the wolf/moose population studies on IRNP, including some of the “how,” I would suggest the following resources:

https://isleroyalewolf.org/overview/overview/at_a_glance.html

https://www.nps.gov/isro/learn/nature/wolves.htm

https://www.npca.org/advocacy/37-wolves-at-isle-royale