The Carbon Cycle: Part Two, the Carbon Process

by Gordon Maclean, Ph.D.

Happy New Year, everyone. Last time I introduced you to the Water Cycle and some important terms used in the discussion of resource cycling, like “sinks” and “retention time.” If you are not familiar with those terms, I will urge you to go back and read “The Water Cycle” because I will be using those throughout this and later articles.

Carbon, an element, is one of the basic building blocks of life on Earth. Carbon, along with the element oxygen, pretty much defines life as we know it. One-part oxygen combined with two-parts hydrogen makes water (H2O). One-part carbon combined with two-parts oxygen produces carbon dioxide (CO2).

Compared to the water cycle, the carbon cycle is a bit more complicated, with many paths to wander through to get the full picture. However, complicated as it is, knowledge of it is essential to understanding the scientific side of almost every environmental issue we are currently facing.

From: https://schooltutoring.com/help/the-carbon-cycle/

From: https://schooltutoring.com/help/the-carbon-cycle/

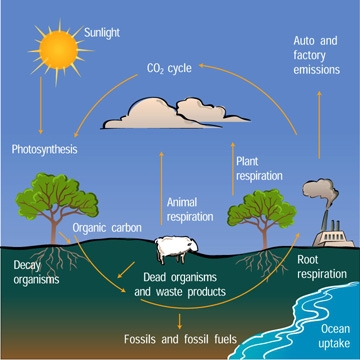

Take some CO2, some H2O, add a bit of sunlight and a process called photosynthesis (literally “to create from light”) and plants on land and in the water will give us basic sugar (CH2O) and oxygen (O2). This is the carbon cycle starting point. In this chemical process, carbon is taken from the air by plants and converted into the material for living cells and the energy to support them. Our atmosphere is one giant carbon sink, mostly in the form of carbon dioxide. Plants have the capability to take carbon out of that sink. As part of that process, plants “exhale,” returning the oxygen part of the carbon dioxide molecule back into the air.

I, as an animal, really appreciate this because my biology consumes oxygen and basic sugar and exhales carbon dioxide and water, releasing energy in the process. Basically, animals “burn” the energy of the sun that is stored as sugar in plants. Alternatively, that plant biomatter can literally be burned via fire. The whole system is a nifty arrangement!

What happens to the carbon in plants? That is where things get complicated. Animals may consume plants directly (cattle grazing, or your salad), or animals will consume the animals that ate the plants. All living matter, plant or animal, eventually dies or is consumed. When that happens, microscopic animals will decompose the now-dead material. Animals release the carbon back into the air to be used by the plants again. All of this is sometimes called the “fast carbon cycle.” Fast in that it takes place during a lifetime.

A tree dies in the forest; it starts to decay. Another tree drops its leaves each fall; they decay. Each of these is returning carbon back into the air in the form of CO2.

In the ocean, a similar cycle occurs; phytoplanktons use the sun’s light along with chlorophyll, and dissolved CO2 in the water to live, grow, and reproduce. Phytoplanktons are microscopic plants that thrive in the topmost layers of all of the Earth’s water bodies. All fish and mammals living in the oceans and freshwater lakes use phytoplankton in a process similar to what occurs on land.

In terms of carbon sinks, besides the atmosphere, there is a massive amount of CO2 that is dissolved in ocean water. It is by far the largest carbon “sink” on the planet.

But not all of the carbon necessarily goes back into the air. In the ocean, some of the carbon sinks to the ocean floor in the form of sediment. There, in an oxygen-poor environment with no microbes to break down the carbon, it collects.

On land, a lot of carbon is taken deep down into the ground by rain and away from the microbes that would otherwise put the CO2 back into the air. The carbon may fall into an oxygen-poor location where microbes cannot survive like a peat bog. Trees falling into such an area can still be removed intact thousands of years later with little or no rot or structural change. This is a true “long retention carbon sink.” (Note that rot is another microbe action returning CO2 to the air.)

Over an extremely long time, from tens to hundreds of millions of years, this carbon can be drawn down thousands of feet below the surface by geologic processes. Over these vast time periods and under tremendous pressures, it will be converted into what we call oil, coal, and natural gas.

Every time you fill your car’s gas tank, you are using energy from the sun that fell on the earth and was converted to living material hundreds of millions of years ago. The use of “fossil carbon” or “long carbon cycle” material is essentially putting CO2 removed 200 to 300 million years ago back into the air.

If you would like more information regarding the “Carbon Cycle” I would highly recommend the following link: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/CarbonCycle.

Next time we will look into reforestation and afforestation and whether they can be used to help get excess CO2 out of the air.