Science Matters

Science Matters

““To see a world in a grain of sand, or heaven in a wildflower.

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand, and eternity in an hour."

~ William Blake

Raging Wildfires

The Role of the Smokey the Bear Campaign and Climate Change

Dr. Gordon A. Maclean

A vast majority of people living today have spent their entire lives under the watchful admonition of Smokey the Bear – “Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires.” The Smokey ad campaign began in August of 1944, and it was, without question, one of the best ad campaigns in history. It may, in hindsight, have been too good. So good that we are now paying the price for some of the policies that resulted.

For most of the next 50 years after Smokey first came on the scene, the concept that “all fire is bad fire” in our woodlands became the driving policy for multiple federal and state agencies tasked with fire control and suppression. For the most part, those policies achieved what they set out to do, contain all fires, natural (usually lightning ignition) or otherwise, as quickly as possible. And by all means, minimize developed property destruction. To be clear, then and now, after a fire reaches a particular size and intensity, firefighters stop attempts to extinguish a fire and go into “containment” mode.

Well before human presence in this world, fires have been a natural part of global ecosystems. Ancient trees that have been cut down show evidence of surviving repeated fires throughout their lifetimes.

Burn scars (white arrows) in the cross-section of a giant sequoia. The numbers represent the year each fire occurred. Photo: Tom Swetnam. https://foreststewardshipnotes.wordpress.com/2017/06/01/fire-and-forest-health/

Burn scars (white arrows) in the cross-section of a giant sequoia. The numbers represent the year each fire occurred. Photo: Tom Swetnam. https://foreststewardshipnotes.wordpress.com/2017/06/01/fire-and-forest-health/

Note that in the fires shown on the image above, the frequency of fires was approximately once per human generation, and given the time frame, there would have been no attempt to contain or limit the fire’s extent.

The “Smokey Issue,” as I will call it, is that the successful fire suppression efforts post-World War II resulted in a LOT of undergrowth build-up in our forests, especially in the western states. Normally, periodic fires would have gone through and killed back shrubs and smaller trees, keeping the fire fuels small and low to the ground. The “Smokey Issue” allowed those trees and shrubs to grow larger and thicker, giving any eventual fire that would come along a LOT more fuel to work with and resulting in fires that would burn hotter, longer, and with a much higher likelihood of “crowning.” Crowning is when the fire transitions from a ground-based event to something taking place in the tree crowns.

Many species of plants and trees require fire as part of their natural life cycle. For trees, most of the western pines and many of the eastern pines have “serotinous” cones that can remain in the tree crowns for decades. These cones REQUIRE fire to open up so that the seeds drop from the crown and get into the earth, germinate, and grow. These trees also tend to have very thick and fire-resistant bark, allowing them to survive your “run-of-the-mill” once in a generation fire.

By the way, these small fires are fantastic for the soil. Fires also release vast amounts of nutrients tied up in the surface layer waiting to decompose (see my articles on Carbon Cycling for further details.)

These advantages and built-in adaptations of nature were inadvertently bypassed when the “Smokey Issue” came about. The fuel build-ups from fire suppression not only caused the hotter fires they, kill trees, burn up the next generation of seedlings and sterilize the forest soils with their intense heat.

Fire suppression policies started to change in the 1990s. There was an awareness that large, destructive forest fires were becoming more frequent and more destructive. It became general policy to let fires burn on a case-by-case basis, provided they did not threaten lives or private property. But we are still stuck with the issue of the fuel loads at ground level.

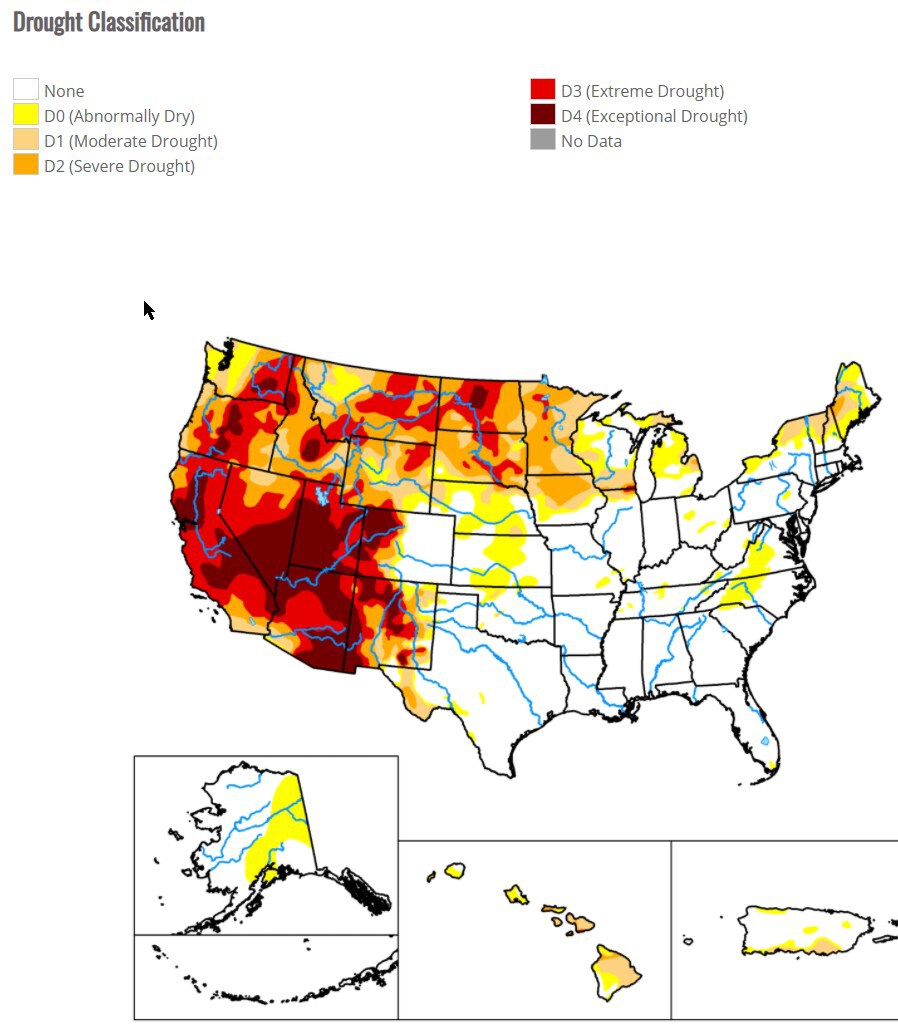

All of this discussion so far has set aside the issue of climate change. There is no question that one serious aspects of climate change is that the western half of the US has been experiencing decreased rainfall, along with increased temperatures over the past several decades. The current western drought began in 2016 in southern California (left map) and has spread across the entire west and into the northern plains (current, right map). Drought maps and archive material canbe found at https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/

Source: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/Maps/ComparisonSlider.aspx

With the widespread drought conditions making ground fuels and foliage tinder dry, any source of ignition is now considered dangerous, if not expolsive. And with many areas have not had a fire in 80 years or more, the areas in orange, red and dark red on the right hand map above will be extremely vulnerable to catastrophic fires until significant rains or snows reduce the threat.

It should be noted that winter in most of these areas will at best provide a respite. The only real relief from drought such as this is a prolonged period of moisture that can replenish the plantlife and the top 15 to 20 feet of soil.

As I write this, the National Interagency Fire Center (https://www.nifc.gov/fire-information/nfn) reports that, currently, 80 large active fires have burned more than 1.1 million acres in the US. For the year, there have been almost 35,000 wildfires that have burned over 2.5 million acres. That is over 4,000 square miles, about 80% the size of the state of Connecticut, just this year alone. For the most part, these are the destructive fires caused by past fire suppression, not the healthy regenerative fires to which forests were adapted.

So, we are in this mess; how do we get ourselves out of it, short of burning the forests to the ground? The answer is, literally, fight fire with fire. But this strategy has to be done in a controlled, thoughtful manner. The most common approach is by prescribed burning, intentionally starting fires in conditions that make it easy to maintain the intensity and extent of the fire. Prescribed burning usually occurs when conditions are damp enough to keep the fire from getting too hot yet are hot enough to burn away the excess fuel laying on the ground, and with a full crew of trained professionals to help keep hot spots from developing.

There isn’t a quick solution here. It took us several generations to get to this point, and by the looks of climate change, things are likely to worsen before they get better. Until that time, we are likely to face the annual smokey haze covering a good portion of the continent. Right now, living in Michigan, I have a yellowish smokey sky from the Oregon fires. These conditions serve as a reminder that we can and have changed life on a global scale. Nature has the ability to recover and self-correct if we give it a chance. But will we like the time scale it requires and the conditions until that happens?

For real-time updates on forest fire status and their resultant air quality issues, please visit https://fire.airnow.gov/

Previously...

- Science Matters: Angry Weather: Heat Waves, Floods, Storms, and the New Science of Climate Change

- Science Matters: An Immense World

- Science Matters: Fractals in Nature

- Science Matters: Fibonacci: Nature’s Mathematics

- Science Matters: Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events and You

- Science Matters: Raging Wildfires

- Science Matters: Wolf-Moose Population Studies

- Science Matters: Bird Vision

- Science Matters: Greenhouse Gasses: How They Work

- Science Matters: Reforestation and Climate Change

- Science Matters: The Carbon Cycle: Part Two

- Science Matters: The Carbon Cycle: Part One